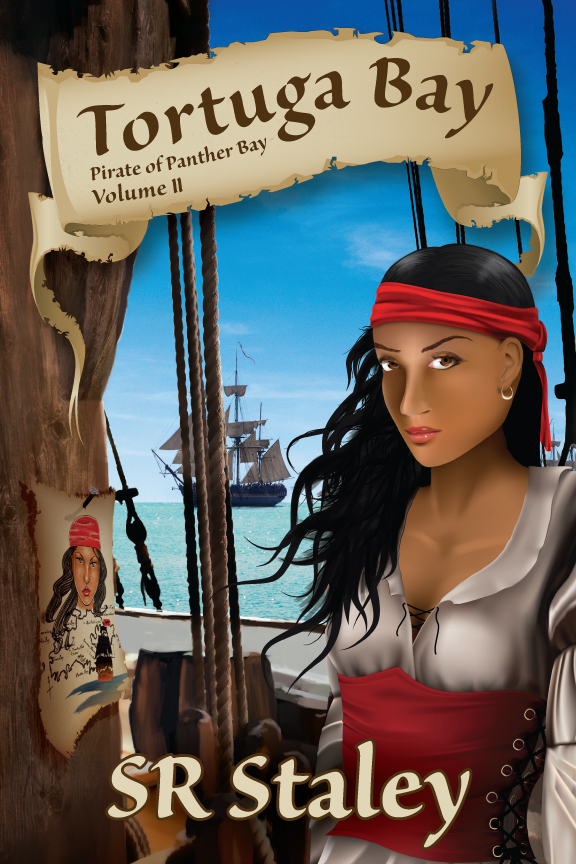

I recently watched Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales and had to once again take a deep breath. The Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise, I reminded myself, is intended for entertainment, not historical accuracy (my review of the film is here). As a social scientist and writer of historical fiction (The Pirate of Panther Bay, Tortuga Bay), I have to step back and remind myself that I take liberties when writing my books, too. Nevertheless, the films play loose with pirate history, and those misrepresentations should be acknowledged.

I recently watched Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales and had to once again take a deep breath. The Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise, I reminded myself, is intended for entertainment, not historical accuracy (my review of the film is here). As a social scientist and writer of historical fiction (The Pirate of Panther Bay, Tortuga Bay), I have to step back and remind myself that I take liberties when writing my books, too. Nevertheless, the films play loose with pirate history, and those misrepresentations should be acknowledged.

Nevertheless, these deviations from historical fact should be intentional and deliberate, not a result of carelessness or lack of interest. So, I have put together a list of five historical inaccuracies promoted or used in Dead Men Tell No Tales that may serve the plot but probably make historians cringe. This is not to say that the director, screenwriters, or producers were reckless, negligent, or didn’t care. Rather, this short list just provides a little real world correction to impressions that may have been left by the movies themselves based on what we “know” historically about Caribbean piracy.

- The ships are too big. Most pirate vessels were small, often one-masted schooners, because they needed to be nimble, fast, and navigate shallow waters. Larger vessels with multiple gun decks were slower and harder to maneuver. They were also easier to run aground. They were best used for blockades or large fleet battles. Hence, these larger ships were called “ships of the line” because they would be arrayed in lines, bow to stern, to engage the enemy. That’s the way fleets did battle up until the 20th century. Pirates were usually solo actors, like Jack Sparrow. A few, such as Blackbeard, were able to command multiple ships. But even Blackbeard’s ship, Queen Anne’s Revenge, was a frigate without the multilevel gun decks depicted in the films. Frigates were among the larger warships designed for speed, agility, and firepower.

- The ships are too fast. Numerous scenes show larger ships of the line overtaking similar sized ships. While some of this can be chalked up to the fantasy elements of the film, in reality ships would pursue each other for days because the differences in speed were only 1 or 2 knots among similar sized vessels. The ships in the films are large, multi-deck warships that would be lucky if they could muster 10 or 12 knots under full sail. Schooners, brigs, and frigates were smaller vessels with relatively more sail area, and were designed for speed. A frigate, for example, could achieve speeds as high as 17 knots. (This is one reason why Isabella commands a brig in The Pirate of Panther Bay and Tortuga Bay.)

- Jack Sparrow is a sad excuse for a pirate captain. Pirate historians would be scratching their heads wondering why his crew continues to sail with him. He is an ineffective, bumbling criminal. He can’t even rob a bank effectively. Historically, pirates raided and plundered towns routinely. In fact, the fort in St. Augustine, Florida was constructed as a direct response to pirate raids on the town. Captains had to be effective leaders to earn the respect of their crews. In the films, Jack Sparrows crew follows him through friendship, loyalty, and pity.

- Pirate captains were respectful of their crews. While pirate captains routinely used fear, intimidation, and violence against their targets, they had little scope to use the same tactics against their crew. The tyranny Barbossa uses against his crew would not have been tolerated, although the riches may have given him more latitude than usual. Pirates were ruthlessly rational and tactical, using violence to achieve specific ends. A democratically agreed upon set of Articles served as a binding constitution that provided transparent ways to distribute the booty in shares. Economist Peter Leeson has an excellent, accessible book on this called The Invisible Hook. (Or listen to the podcast with Peter at Under the Crossbones here.) Pirate crews were volunteers, and they elected their captains. A pirate captain in the Caribbean would not exact tribute from his crew without risking immediate defection. The crew could always elect another captain.

- The British Navy’s anti-piracy campaign was professional. In the movies, the British colonial administrators are driven by deeply held beliefs in legend and superstition. In reality, the British successfully purged pirates from the Caribbean was eminently practical—they wanted to protect the shipping lanes for commerce. The British were remarkably successful, bringing the so-called “Golden Age of Piracy” to an end by 1730s. They achieved this through concentrated force, the ruthless pursuit of pirates, and a liberal willingness to hang anyone caught in the act of piracy. Pirates (as well as sailors generally) were very superstitious. So, this focus on legend and mysticism fits well within pirate lore and even beliefs among common sailors. However, in terms of colonial policy and strategy, the British Navy took a highly professional approach to ending piracy in the Caribbean.

Writing historical fiction puts authors in a dilemma—often history, or what we “know” to be historical, is at odds with a good story. This appears to be the case in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies where battles between big ships seems to carry more dramatic effect. Authors of historical fiction have to make these trade-offs as well. For example, we have no historical records that a woman commanded a pirate ship in the Caribbean, but Isabella does in the Pirate of Panther Bay series. Nevertheless, a woman in a leadership position, an escaped slave nonetheless, creates dramatic tension that moves the story. I have tried to nest the story in the real historical context of the times (and appear to have done this based on reviews).

I wonder if a more nuanced approach to storytelling in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies might have allowed a bit more historical accuracy without sacrificing dramatic effect. I have found smaller vessels provide more opportunities for dramatic tension and conflict that larger ships. This is why I found the original escape and pursuit of Jack Sparrow somewhat more satisfying n the Curse of the Black Pearl—at least the ships in the movie were closer to the right scale. But it’s also why Isabella continues to captain a smaller ship in the book series.

For more great history and all things pirate, check out Under the Crossbones, a podcast hosted by Phil Johnson. Phil interviews me in Episode 20 here, and he’s up to 92 episodes.

More details on the Pirate of Panther Bay series, including classroom guides and information on the literary awards the books have earned, can be found here.

The Pirate of Panther Bay is available at amazon.com here.

Tortuga Bay is available from amazon.com here.