At first blush, Roma is the kind of movie critics and industry types love. Most American filmmakers can probably tick off with ease the reasons why Alfonso Cuaron’s film is destined to become an industry classic. The cinematography is fantastic, the frame-by-frame attention to detail is stunning, the director’s decision to film in black and white was bold, the existential approach to telling the story (using the point of view of a young domestic servant’s life — Cleo, played by Yalitza Aparacio — as a live-in maid and nanny to a upper middle class family in Mexico City) evokes empathy and reflection. The fact that Cleo is also of indigenous ethnic origin, and apparently Aparicio is the first indigenous woman to be nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award, is icing on the cake.

For (American) audiences, however, here’s the rub: The movie is slow moving, appears to meander, and borders on boring. The film has very little action, and even less plot. Roma appears to be about the characters and their arc over the course of the film.

Not surprisingly, critics are heaping praise while audiences are less enthusiastic. At Rotten Tomatoes, 96% of critics rate Roma fresh while audiences are less enamored, with just 73% giving it similar ratings. If audiences had more backstory, their appreciation for the movie might improve. A little Mexican political and economic history, almost all of it ignored by most American reviews (which describes it as a semi-autobiographical film) helps us understand why Roma is, in fact, much more.

Roma is more than an art movie.

Set in 1970 and 1971, the movie takes place ten years after the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) started Mexico’s “Dirty War”. The government repressed leftist organizations, students, and anti-PRI political opponents as it used increasingly authoritarian tactics to maintain control. The tactics were violent, leading to hundreds of deaths and thousands of injuries as the PRI become more authoritarian. Most notable for Roma’s story may the Corpus Christ massacre in June 1971, which becomes a critical plot point.

This background is actually fundamental to understanding the movie. I could see more clearly the human drama unfolding in the scenes. Cleo’s passive role (and understated acting) in the family, despite her central role as its anchor, is more fully understood. The relationship between Cleo, her host family, and her co-workers reflect the socioeconomic (and political) tensions of the time. Cleo is from a poor, indigenous village, but she works in Mexico City for a well-educated professional family. The father is a medical researcher and doctor, and the mother is a biochemist. Cleo’s role at the center of the family dynamics is put in stark contrast to her impoverished, less sophisticated and uneducated background. At the same time, we see the importance of Cleo supporting her own family through her work in the city.

Meanwhile, wealthy land owners (and relatives to Cleo’s host family) are working with, or at least complicit in, the government’s land expropriation policies directed at poor indigenous villagers and small farmers. The conflicts and tensions between rural and urban ways of life play out in important ways as the middle-class family dynamics deteriorate and Cleo is faced with a traumatic choice that will alter the future of her life and relationship to her host family. Several scenes specifically draw on the repression and chaos surrounding the events of the Dirty War, and how government policy played out in class tensions, inequities in political power, and the fragile nature of property rights in Mexico. Understanding this, Cuaron’s imagery is even more salient and crucial to the film.

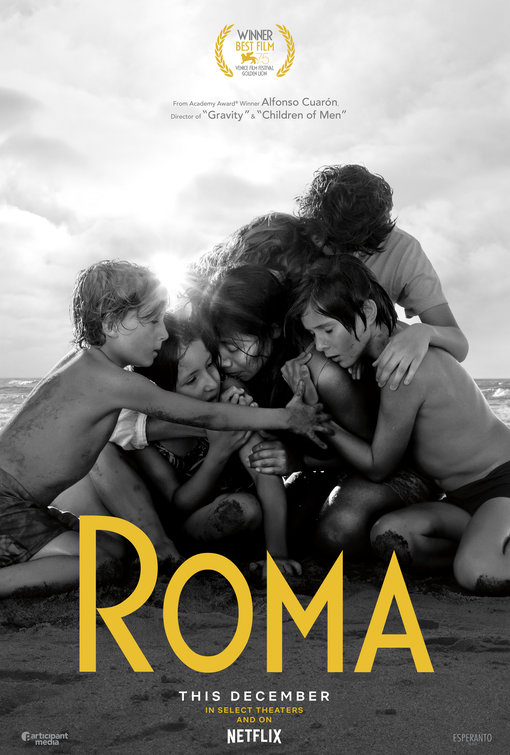

I will not be surprised if Roma takes several major awards during Oscar night, including Best Picture and Best Director, most of them well-earned. While the inspiration for Cleo is in fact drawn on Cuaron’s family and his life growing up in the Colonial Roma neighborhood of Mexico City, and he no doubt drew extensively on his personal experiences growing up in the neighborhood, the film is a very subtle and sophisticated use of visual storytelling to engage in social commentary. I just needed to know more about Mexico’s political history to really appreciate full breadth of what Cuaron accomplished on the screen.

1 thought on “Roma shines with a little help from Mexican history”

Comments are closed.