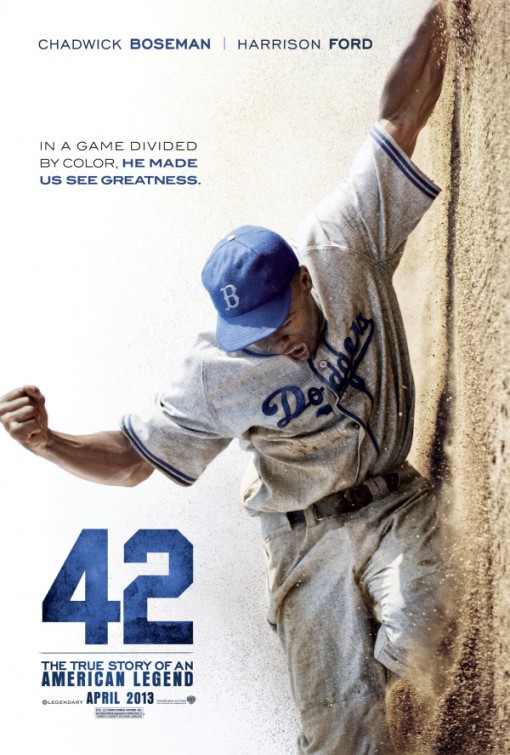

The untimely and unfortunate death of Chadwick Boseman finally prompted me to watch his break out performance in the 2013 American drama, 42. The story, as the number implies, chronicles the role Jackie Robinson played in breaking the color barrier in major league baseball when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. But this movie is about more than major league baseball. It’s a chronicle of a pivotal moment in American history and race relations.

42 Is About More Than Baseball

Well scripted and tightly directed by Brian Helgeland (L.A. Confidential, Mystic River), 42 features a thoughtful, emotional, and intense performance by Boseman.

At the time, African American ball players were relegated to the Negro leagues. Racism prevented them from playing in the majors. Importantly, baseball’s racism was not legally imposed; it was an informal rule that widely accepted, practiced, and enforced. While Jim Crow laws made integration difficult since most training camps and several clubs played in the South, integration was possible.

Jackie Robinson was born in Cairo, Georgia, just over the Florida state border north of Tallahassee. But Robinson’s mother moved west to California after his father abandoned the family. Importantly, Robinson grew up in non-Jim Crow Southern California. While racism existed, the rigid rules and codes did not force the separation required by law and culture in the South.

Racism and the U.S. Military

Robinson eventually attended UCLA and became the first athlete to win varsity letters in four sports (basketball, football, track, and, of course, baseball). After UCLA, he worked briefly for a government funded youth program and then played semi-professional football in Hawai’i and California. Notably, these teams were integrated.

World War II interrupted his athletic career, and Robinson joined the U.S. Army. He started in a black cavalry unit, and became one of the few black soldiers to be accepted into Officer Candidate School. Commissioned as a lieutenant in 1943, Robinson was transferred to the first Black tank battalion, the 761st “Black Panthers”.

While he never made it to the battlefields, Robinson became well acquainted with the need to stand up for his civil and human rights. Like many other soldiers growing up in the non-Jim Crow north and west, he buckled under the social pressure, deferential expectations, and local codes that required strict subordination to whites. Sometimes at the penalty was death, as in the shooting of a black soldier by a white bus driver. (Robinson was subsequently acquitted by an all-white jury). Black soldiers were routinely harassed, bullied, and intimidated by citizens, law enforcement, and even white military police and soldiers within their own units. Rank didn’t matter.

When Lieutenant Robinson refused to move to the back of a bus to make way for civilians boarding in Fort Hood, Texas, he was detained, arrested and court martialed. The arrest occurred even though the bus line was commissioned by the U.S. Army as desegregated transportation to avoid southern harassment. Ultimately, Robinson was acquitted (by an all white panel of nine officers), but the delays meant he lost out on his chance to serve with his unit in Europe.

An excellent overview of Robinson’s arrest and court martial, as well as the heroic actions of this unit in Europe, are artfully chronicled in Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s book (co-written with Anthony Walton), Brothers in Arms: The Epic Story fo the 761st Tank Battalion, WWII’s Forgotten Heroes.

Jackie Robinson and Racial Equality

The details of Robinson’s backstory in the Army and professional athletics prior to World War II are largely ignored in the movie. But they are consequential for the film and understanding Robinson’s legacy. While the movie 42 maintains the spirit of Robinson’s resolve, the movie departs in important ways to support the story in the film.

When Brooklyn Dodgers owner and manager Branch Rickey (Harrison Ford) decides to sign black players in an effort to break the informal color barrier, his assistant manager and scout (Toby Huss) points out Robinson has a temper. He was court martialed for insubordination, he notes, although he was acquitted and received an honorable discharge. Rickey sees the incident as an advantage: Robinson has the fortitude to withstand the racism and pressure of being the first Black to play in the majors.

However, in a key plot point, Rickey confronts Robinson with the need to control his temper on and off the field. Any fights or hostility will doom the experiment in desegregation. Rickey, in essence, is lecturing Robinson on the importance of nonviolent resistance. Stay focused on the job on the field, he says, and they will accomplish the larger goals of desegregation. In real life, Robinson had already learned this lesson and his personality was well suited to withstanding this kind of pressure. In the movie, Robinson appears to be persuaded by Rickey as a mentor and signs the contract.

Desegregating More Than Major League Baseball

Any romantic notions of a non-racist North are quickly dispelled in 42, accurately. Rickey’s attempt to break the color barrier generated across the board resistance and hostility. Robinson’s presence at one point leads to a hotel refusing accommodations to the Dodgers. Robinson is assaulted with taunts from the stands, other players, and opposing coaches. Robinson must also grapple with racist revolts among teammates who refuse to play with a black player.

Rickey’s resolve doesn’t waver, although, in the movie, the tension pushes Robinson to a breaking point. Robinson did not break in real life, according to most accounts, but the event serves the story of the film and the spirit of Robinson’s trials if not historical fact.

The Bottom Line

Overall, the movie does an excellent job using contrasts between segregated and unsegregated regions of the country, rampant racism among players and fans despite stellar on-field performance, and the pressures of the business of baseball to force reformers to buckle under pressure to keep the major leagues white.

In addition to a tight script, the drama keeps audiences engaged and focused on the story. While Ford and Boseman received most of the accolades when the movie was released, excellent performances by Nicole Beharie as Rachel Isum Robinson, Chistopher Meloni as the gruff and impolitic manger and coach Leo Durocher, Andre Holland as black journalist Wendell Smith, and Lucas Black in a pivotal role as Pee Wee Reese, among others, keep the story and movie moving forward.

42 is more than a story about Jackie Robinson and desegregating major league baseball. It’s also a well told story about the contradictions, paradoxes, and inhumanity of racism at a critical period in the United States. The Post-World War II era would usher in the modern Civil Right Movement. Eventually these efforts would result in the dismantling of nearly 100 years of Jim Crow.

Another excellent movie exploring the nuances of America’s color line is Green Book. My review can be found here.