I once read in a book on writing screenplays that movies are 80% visual, and this is one reason why movies are so successful at connecting with audiences. Humans are visual animals, and they interpret their surroundings based on sight. All the senses are important, but when it comes to identifying or assessing threats, or devising strategies, we rely on our eyes more than any other sense.

I once read in a book on writing screenplays that movies are 80% visual, and this is one reason why movies are so successful at connecting with audiences. Humans are visual animals, and they interpret their surroundings based on sight. All the senses are important, but when it comes to identifying or assessing threats, or devising strategies, we rely on our eyes more than any other sense.

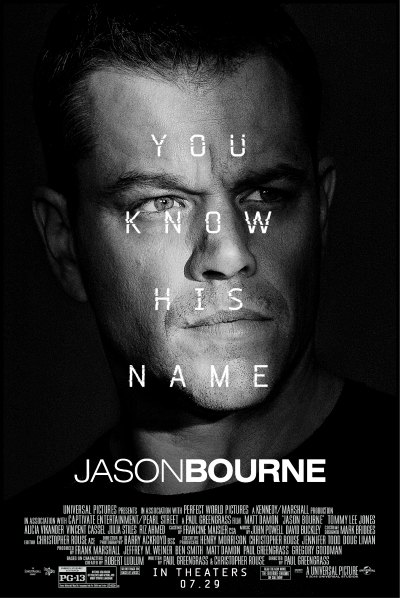

I was reminded of this while watching the most recent Jason Bourne film based on the Robert Ludlum character and novels. The film is a direct sequel to The Bourne Ultimatum, and it’s aptly titled because the story in this movie is really about Jason Bourne trying to uncover his true identity. The entire cast–Matt Damon, Tommy Lee Jones, relative newcomer Alicia Vikander and others–does a great job save for Julia Stiles playing Nicky Parsons (whose performance I thought was rather wooden). The plot is fast paced with two extended car chases, which should be enough to keep teenagers in age and heart more than engaged. In other words, Jason Bourne is an example of a big-ticket action film that’s also well produced on a big budget.

But that’s not what really impressed me.

Rather, the first 15 or 20 minutes of the film seemed like a masterful example of visual storytelling. We must have been five or ten minutes into the film before any meaningful dialogue was spoken by the main characters. Yet the entire story was essentially set up with visual cues and action.

The opening scenes have Nicky Parsons (Stiles) hacking into the CIA’s database to download files on the covert assassin programs run by the agency’s director Robert Dewey (Tommy Lee Jones). All she says, in effect, is the password to get into the warehouse were a platoon of hackers is working in a wikileaks manner to uncover dark secrets held by government. We immediately know she is active in trying to identify and expose the covert CIA assassin programs–Blackbriar, Treadstone–when she discovers a new program Iron Hand which is the surveillance programs of all surveillance programs. She also uncovers files that identifies Bourne’s father as a key player in setting up the initial Treadstone program. All this is done through Nicky’s actions–her expressions as she discovers different components, her fingers as she works the keyboard, the computer monitor as files and file folders appears–as movie goers look over her shoulder as she hacks away. She clicks on folders, opens and scans files, downloads them, and then escapes after the CIA identifies the hack and shuts the operation down. Thus, we, as onlookers, put the pieces together. We discover that the CIA is active in its covert program, the agency is more ruthless than ever, Nicky is hot on the trail and scared, and she still is doing a lot of legwork for Bourne. She cares.

In another highly effective exercise in visual storytelling, driven in part because Jason Bourne is a man over very few words, the director (Paul Greengrass) establishes that Bourne is alive and well, but living under the radar. Visual scenes with very little dialogue other than crowds yelling words depict Bourne in underground, presumably illegal, fights in Greece. That’s how Bourne now earns his living–cash in a cash society so nothing can be traced. No words are spoken by Bourne, but we know he is living a gritty, exhausting, meticulously low profile existence. And he’s tough and fit.

These are just a few of the sequences that depict a talented director and filmmaker practicing the art of “Show don’t telll.” For those interesting in film as visual storytelling, and thinking outside the box for ways to “show don’t tell” in narrative fiction writing, studying the first 15 minutes of Jason Bourne is well worth the effort.